Aspect orientated programming for fun and profit

What is AOP (Aspect orientated programming)?

Before we kick off a quick delve into Aspect orientated programming, it would be good to make sure that we’re all on the same page with regards to what we mean by the term AOP. There are quite a few references that you can use in order to define AOP [1] [2] [3], but for the purposes of this article, we’ll use the following definition: A module that intercepts a call to a function in order to apply cross-cutting-concern functionality in a consistent manner either before or after the call. But what does this actually mean? The upshot of AOP is that we can run common code e.g. logging & tracing statements before a function executes to prevent us having to write those log statements manually for each function and employing a copy-paste procedure. If you are familiar with the OO design pattern: the decorator then the idea of a component wrapping up another but exposing the same interface should come as too much of a surprise.

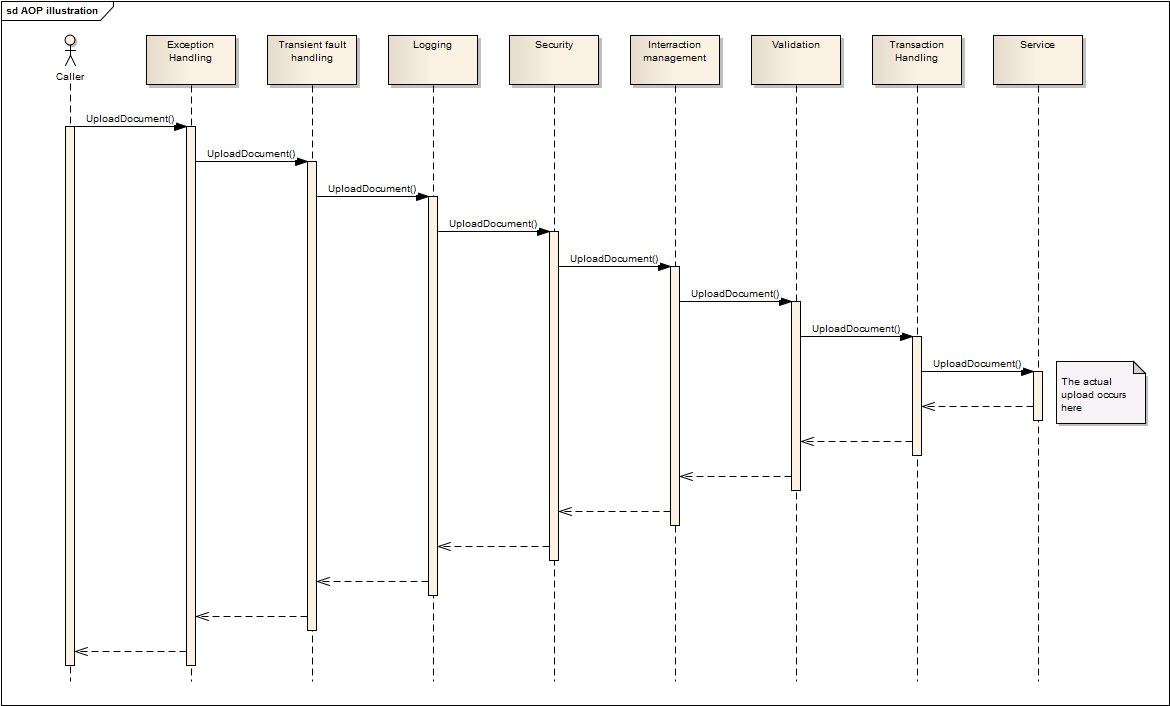

When you get comfortable with the idea of a module running before and after the function you called, you then start to realise that you can have multiple modules intercepting the same function call. At this point in time, perhaps a diagram might help.

This diagram shows how different aspects/modules can be structured before the service call to all provide common functionality that would otherwise be duplicated throughout your code. Whilst the diagram shows quite a few aspects in use, the reality is that you would tailor the order and number for your own specific needs.

What benefits does AOP provide?

So now we understand what AOP is the question I’m sure you’re all thinking is why do we need it? After all new tools and techniques are fairly meaningless unless they give you some appreciable benefit! AOP comes with a couple of major benefits that can be loosely defined as the following:

- Minimise code duplication and repetition within your domain specific code. This then has the benefit of cleaning up the domain code to ensure that it is only responsible for achieving the one job that it was designed to do.

- Move cross cutting concerns into compartmentalised modules that can be applied consistently across your code-base. The application of these aspects/modules can then be controlled in a consistent fashion across the solution to ensure that even new functions that are written can benefit from the cross cutting concerns without having to spend too much time duplicating existing code.

Imagine you had a (completely fictitious) function whose responsibility was to upload a file from one location to another and add a database entry for auditing purposes, simple right? Now imagine that the very same function needs to be able to perform the following:

- Write a detailed logs containing the input parameters and the returned values (for audit and support purposes)

- Write detailed trace information containing how long the entire function took to run in milliseconds

- Only allow users with certain roles to call the function

- Only allow non-admins to upload a file at most every 5 minutes

- Validate the request object to ensure that bad data is not being uploaded

- Handle any transient faults and retry the function if it fails with a transient error

- Handle any errors and add the appropriate logging to aid support

- Make sure that all interactions to the database are handled within ine transaction so that if the upload fails, the data in the database accurately reflects the upload process

This is just the sort of ‘enterprisey’ suite of requirements that exist in the real world. Developers faced with this have (generally speaking) two main choices:

- Write everything in one upload function so that that whole piece of functionality can be said to meet the requirements in its entirety

- Stop, think about the requirements and design a solution that follows the SOLID design principles. Design a solution that is simple, non-repeating and allows the upload function to fulfil the ‘Single responsibility’ portion of the SOLID acronym namely the upload of a file.

Just try and imagine for a moment if you were the developer in question who was asked to write this feature. Try to imagine what the code would look like if you followed option one. Fortunately, you don’t need to try very hard because I have written a little sample which isn’t based on any actual code, but it is indicative of the style of programming prevalent within many organisations. This can be seen below

All cross-cutting concerns & requirements existing in one function:

using System;

using System.Diagnostics;

using System.IO;

using System.Security;

using System.Security.Principal;

using System.Threading;

namespace AOP

{

public class ProceduralCode

{

public dynamic Log { get; set; } // Only used to get the code to compile & illustrate a point

public dynamic JsonSerializer { get; set; } // Only used to get the code to compile & illustrate a point

public dynamic Database { get; set; } // Only used to get the code to compile & illustrate a point

public dynamic TransactionManager { get; set; } // Only used to get the code to compile & illustrate a point

public UploadDocumentResponse UploadDocument(UploadDocumentRequest request, bool recursiveCall = false)

{

// LOGGING: Log the start of the method call

Stopwatch traceTimer = Stopwatch.StartNew();

Log.Trace("START>> AOP.ProceduralCode.UploadDocument({0},{1})", JsonSerializer.Serialize(request), recursiveCall );

UploadDocumentResponse result = null;

try

{

// SECURITY: Check that the user can access this function

IPrincipal currentUser = Thread.CurrentPrincipal;

if(currentUser == null)

{

throw new SecurityException("Thread.CurrentPrincipal must be set to call: AOP.ProceduralCode.UploadDocument");

}

if (!currentUser.IsInRole("DocumentationManager") && !currentUser.IsInRole("Admin"))

{

throw new SecurityException(string.Format("CurrentUser ({0}) must have the role DocumentationManager or Admin", currentUser.Identity.Name));

}

// VALIDATION: Validate that the input is correct

if(request == null)

{

throw new ArgumentException("Arguement 'request' cannot be null", "request");

}

if(!File.Exists(request.SourcePath))

{

throw new FileNotFoundException("Cannot locate file to upload", request.SourcePath);

}

// INTERRACTION MANAGEMENT: Throttle upload requests to be once per user per 5 minutes (only for non-admins)

DateTime lastUploadTime = Database.GetLastUploadTime(currentUser);

if((DateTime.UtcNow - lastUploadTime) < new TimeSpan(0,5,0) && !currentUser.IsInRole("admin"))

{

throw new ApplicationException(string.Format("User {0} cannot upload a file more than once per 5 minutes. Last upload time was {1}", currentUser.Identity.Name, lastUploadTime));

}

// Record the fact that the user has tried to upload the file

Database.LogUserActivity(currentUser.Identity.Name, request);

// TRANSACTION MANAGEMENT: Use a transaction to update the database

using (var transaction = TransactionManager.CreateTransaction())

{

string uploadPath = Database.GetUploadPath(transaction, currentUser.Identity.Name, request);

Database.StoreUploadFileRecord(transaction, currentUser.Identity.Name, request);

File.Copy(request.SourcePath, uploadPath);

result = new UploadDocumentResponse();

transaction.Commit();

}

// LOGGING: Log the return value from the method along with the total elapsed execution time

Log.Trace("STOP>> AOP.ProceduralCode.UploadDocument returned ({0})", JsonSerializer.Serialize(result));

}

catch(TransientException e)

{

// TRANSIENT FAULT HANDLING:

if(recursiveCall == false)

{

// Try the method again after 100ms

Thread.Sleep(100);

return UploadDocument(request, true);

}

else

{

Log.Error("Two Transient exceptions", e);

throw;

}

}

catch (Exception e)

{

// EXCEPTION HANDLING

Log.Error("Unrecoverable error", e);

throw;

}

finally

{

// TRACING

traceTimer.Stop();

Log.Trace("AOP.ProceduralCode.UploadDocument finished in {0} milliseconds", traceTimer.ElapsedMilliseconds);

}

return result;

}

}

public class UploadDocumentRequest

{

public string SourcePath { get; set; }

}

public class UploadDocumentResponse { }

public class TransientException : ApplicationException { }

}

I think that we can all agree that the above code snippet is about as far away from ‘Single responsibility’ as it’s possible to get. Just by looking at the using statements required for this one function you should be able to see that this is doing far too much! Granted that this isn’t actually production code and was written to illustrate a point, but, I have seen plenty of production classes and functions that follow this pattern in a much more convoluted manner than the above UploadDocument. If one function has this extensive battery of requirements that are associated with it, then the odds are pretty good that there will be other functions with similar functional needs. Using the above methodology means that you will likely see all sorts of snippets of code copied-and-pasted liberally throughout your application to allow all the methods the same functionality. Whenever a developer is copying-and-pasting, its highly likely that the developer will forget to change a value or two resulting in some weird behaviour, how many times have you seen a function with a log statement belonging to another function but has been copied and pasted incorrectly. The result: one very confusing log!

Just imagine if you were writing a unit test for the beast above, each and every unit test would need to:

- Set the current thread principle to something that is able to call the function.

- Create a valid request object. This includes a valid file to upload

- Mock out the database object (you are using Mocks aren’t you?!) to ensure that the rate limiting check passes

- Mock out the Transaction manager to ensure that a dummy transaction is created

All that to just test that a file can be moved from one location to another…to me that seems like an awful load of work!

Now imagine if the cross cutting concerns were added to reusable aspects:

namespace AOP

{

class AopExample

{

public dynamic Database { get; set; }

public dynamic TransactionManager { get; set; }

// NB: the attributes are an easy method of allowing the aspects to check if any work is required

[Transaction]

[Roles("Admin", "DocumentationManager")]

[ValidateParameter("request", false)]

[UserRateLimit(5)]

public UploadDocumentResponse UploadDocument(UploadDocumentRequest request)

{

UploadDocumentResponse result = null;

var currentUser = Thread.CurrentPrincipal; // Even this can be improved!

// Record the fact that the user has tried to upload the file

Database.LogUserActivity(currentUser.Identity.Name, request);

try

{

string uploadPath = Database.GetUploadPath(currentUser.Identity.Name, request);

Database.StoreUploadFileRecord(currentUser.Identity.Name, request);

File.Copy(request.SourcePath, uploadPath);

result = new UploadDocumentResponse();

}

catch (Exception e)

{

TransactionManager.HandleException(e);

throw;

}

return result;

}

}

}

Wait, what… where’s all the code gone?! Don’t worry, the functionality is still there, it’s just not all in the same place. In this example there will be a number of aspects that will have intercepted the call to UploadDocument and apply the functionality as described in the aspect and the attributes above the function. So what might one of these aspects look like? I’m not going to go through them all, but in the next section we’ll look at the logging example to give you an idea about what to expect. Look at the UploadDocument code, isn’t it cleaner? isn’t it easier to see what the function is trying to achieve? Granted, there’s till some work to do tidying up the function, but as an example you can see it’s possible to significantly reduce the lines of code required in each domain function.

How can we implement AOP?

There are two main ways in which you can implement AOP (within .NET):

- IL weaving by using a tool like Postsharp. The interception is achieved at compile-time to provide you with a fully configured assembly post build. Full disclosure: I haven’t used Postsharp in a production like environment so I can’t comment on it’s effectiveness

- Runtime interception creation by using a tool like Windsor.Castle (or another DI container). Whilst this sounds like a scary thing, it’s not! Due to the fact that I use Castle as a DI container on all my projects, I prefer to hook into the interception mechanism provided by castle (kill two birds with one stone!)

I promised you a look at one of the interceptors (or at least what they might look like) so here it is…

class LoggingAspect : IInterceptor

{

public void Intercept(IInvocation invocation)

{

string methodName = invocation.Method.Name;

string className = invocation.TargetType.Name;

ILog log = LogManager.GetLogger(className);

var stopwatch = Stopwatch.StartNew();

try

{

ParameterInfo[] parameters = invocation.Method.GetParameters();

log.DebugFormat("BEGIN - {0}.{1}({2})", className, methodName, string.Join("'", parameters.Select(x => x.ToString())));

invocation.Proceed();

var returnValue = "<<Void>>";

if (invocation.ReturnValue != null)

{

returnValue = invocation.ReturnValue.ToString();

}

log.DebugFormat("END - {0} returned {1}", methodName, returnValue);

}

catch (Exception e)

{

log.Debug("END - " +methodName+ " threw an exception", e);

}

finally

{

stopwatch.Stop();

log.DebugFormat("TRACE - {0}.{1}:{2} milliseconds", className, methodName, stopwatch.ElapsedMilliseconds);

}

}

}

I’ve deliberately chosen one of the more simple aspects to focus on so it’s possible to see what’s going on. I’ve also chosen to go down the Castle interception route as this is the tool that I’m most familiar with. We can see with the above example that we are:

- Logging the method call start time with the

ToString()representation of all the parameters. - Start a performance

Stopwatchto track how long a function takes. - Proceed to call the function being intercepted

- Either log the return value OR the exception that has been raised

- Log out how long the function took.

The beauty of this level of abstraction is that this logging code can be used to intercept nearly any function and you can guarantee to get consistent log messages for all the intercepted functions. This can then be used to gather metrics about the application at a later date e.g. most used functionality performance profile of the application, all without any expensive monitoring tools.

What sort of cross cutting concerns can AOP help with?

Almost anything you can think of that can occur within most functions in your code-base! Although there are a number of core aspects that can be found in most AOP enabled solutions:

- Exception handling

- Transient fault handling

- Logging & tracing

- Security

- Interaction management

- Validation

- Transaction management

Incidentally, these are all featured in the diagram above!

So why isn’t everyone using this technique?

That’s a difficult question to answer as it might have multiple complex answers, but I’ll do my best to over generalise and come up with a list…

- Developers aren’t comfortable with code that executes without them seeing it in-situ, these types of developers are more comfortable with procedural type functions where everything is located in one big method. This view might also stem from the fact that there is an increased learning curve with aspects as you need to learn where they are, what they do and how they’re applied. I’d argue that once a developer has learnt how the Aspects interact with the code-base, then it actually lessens the cognitive load when trying to write/read a new piece of functionality.

- It’s not appropriate to the problem. Like anything AOP is a tool and using it for every problem might not be appropriate. Once you find yourself writing or copying a cross cutting concern multiple times, this might be a good time to reconsider AOP.

- It’s not available in/pertinent to your particular technology stack. This is the main issue preventing AOP adoption, unless you’re looking to write your own AOP framework!

- Are there any others that I’ve forgotten about? Feel free to add them in the comments below.

Hopefully the article above has impressed the value of AOP within software. Personally, I’ve found it invaluable when managing complexity and designing a well encapsulated solution. If there are any questions you have about any of the above, please feel free to get in touch using one of the myriad of options available.